The English language is a barbarous one, known for plundering other tongues, rich for all its greed. It is precisely this that has made it so adaptable to local cultural and linguistic peculiarities. It’s also what makes the language so damnable, having more exceptions than rules.

Let me develop on some of my daily dichotomies as a sub-editor at Flow.

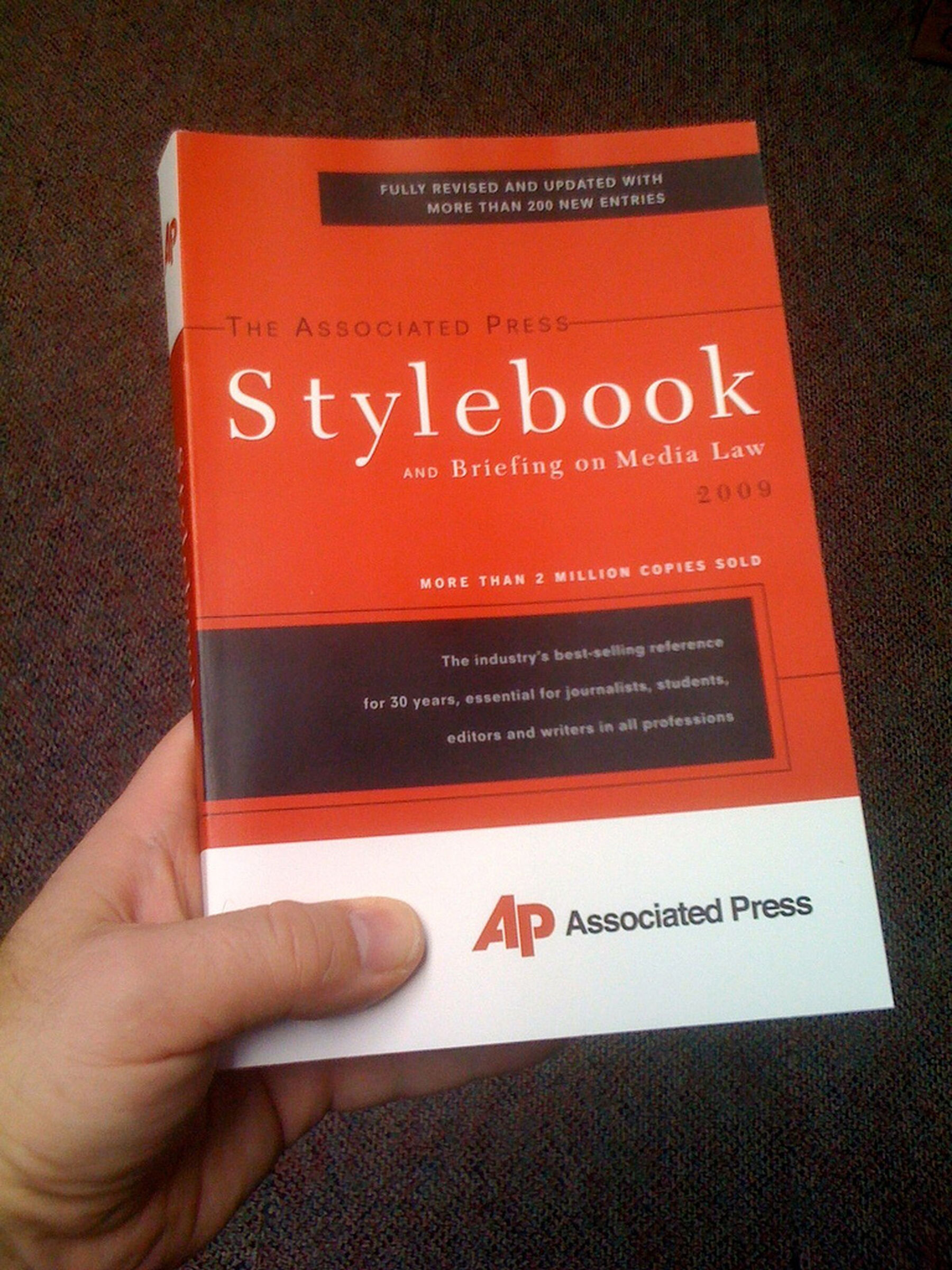

The Associated Press Stylebook (a sub-editor’s bible) would have me italicise all non-English words, except where they have become sufficiently anglicised. “Café” would be a case in point. The Yiddish word, “maven” (a trusted expert), another. Likewise with “yo-yo” from the Tagalog language of the Philippines, and “amok” from the Malay, or “pyjama” from the Hindustani.

But where do words like vuvuzela and makarapa fall? And the term Diski dancing? Are they beyond the English pale? What gets italicised, or sandwiched between inverted commas, or capitalised at the very least?

These are the questions that plague me at night.

The simple apostrophe can be the most dastardly. Is it one devil or many devils who preside over the Cape mountaintop? Devil’s Peak or Devils’ Peak? Supposedly taking its name from the occasion Jan van Hunks, a consummate chain-smoker, outdealt the Devil in a pipe-smoking contest (and so: Devil’s Peak), Table Mountain’s counterpart, and how to refer to it, certainly piqued this devil.

It’s in the seemingly simplest that the real trouble lurks.

Afrikaans says it best: “Stille water, diepe grond [still waters, deep ground].”

Let me give you an example: Queens’ College in Cambridge. The apostrophe falls after the “s”. Why? The college was first founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou, Queen of Henry VI, and refounded in 1465 by Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of Edward IV. Two queens, one college. It’s these kind of scruples by which your weight can be weighed, especially in Cambridge.

This use of the shibboleth (a Hebrew contribution to English, which is another story altogether) or linguistic discrimination has a history of preceding some ruthless behaviour, whether you look to Judges in the Old Testament or the practice of severing the tongues of slaves who spoke no English.

Not that I’m coming at anyone with a machete. Although I might take aim at their words.

Chop-chop.

Ah, this bastardised language that leaves me both bedevilled and bedazzled. I wouldn’t change it for the world.